Some photos send shivers down your spine, even if they weren’t meant to. A harmless snapshot can feel unsettling when viewed through the lens of history or stripped of its context. Why does it feel so eerie? What’s the story behind it?

Throughout time, cameras have captured moments that spark curiosity, unease, and countless questions. These haunting images weren’t created to be creepy, but their mysterious details or forgotten histories make them unforgettable.

Sometimes learning the truth behind them eases the tension—but other times, it only deepens the mystery. Ready to uncover the stories behind these chilling glimpses of the past?

Mountain of bison skulls (1892)

This haunting photo, taken in 1892 outside Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Michigan, captures a shocking moment in history. It shows an enormous mountain of bison skulls, harvested to be processed into bone glue, fertilizer, and charcoal. What makes this image so unsettling is the story it tells — not just about the exploitation of natural resources but about a massive loss tied to colonization and industrialization.

At the start of the 19th century, North America was home to 30 to 60 million bison. By the time this photo was taken, that number had plummeted to a staggering low of just 456 wild bison. The westward expansion of settlers, coupled with market demand for bison hides and bones, fueled a brutal slaughter that decimated the once-thriving herds. Between 1850 and the late 1870s, most herds were wiped out, leaving behind both environmental and cultural devastation.

The towering pile of bones in this photograph isn’t just a testament to industrial greed; it also reflects the deep connection between Indigenous Nations and bison, a connection forcibly severed by this large-scale destruction. The bones, stacked like a man-made mountain, blur the line between natural and manufactured landscapes, a concept that photographer Edward Burtynsky later described as “manufactured landscapes.”

Today, thanks to conservation efforts, roughly 31,000 wild bison roam North America. This photograph serves as a stark reminder of how close we came to losing them entirely—a chilling glimpse into a past shaped by choices that still echo today.

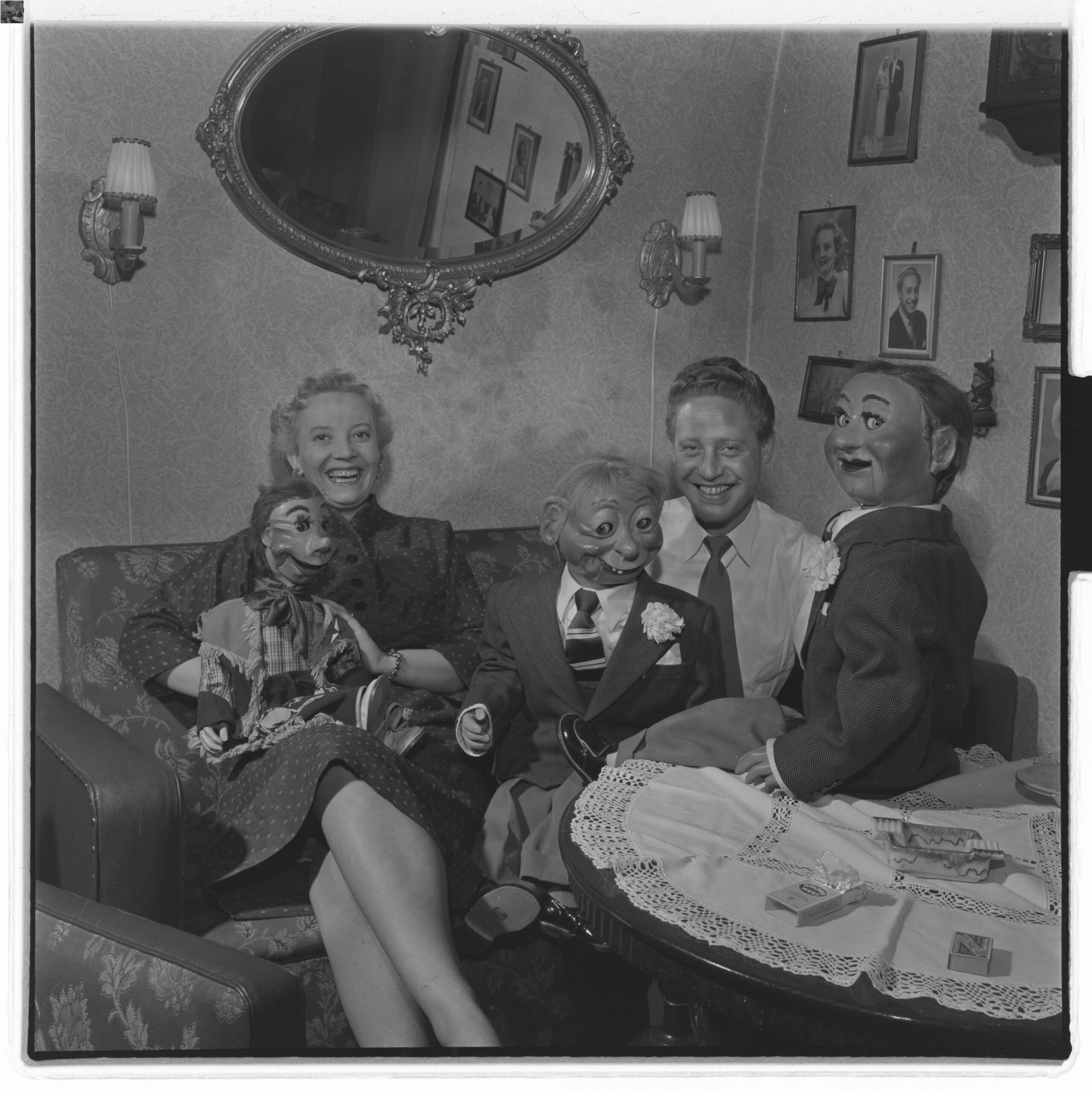

Inger Jacobsen and Bülow (1954)

This mid-1950s photo might seem a little eerie at first glance, but it likely captures just an ordinary day in the lives of Norwegian singer Inger Jacobsen and her husband, Danish ventriloquist Jackie Hein Bülow Jantzen, better known by his stage name, Jackie Bülow.

Jacobsen was a beloved singer in Norway, even representing her country at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1962. Meanwhile, Bülow brought his unique charm and talent as a ventriloquist to audiences at a time when the art form was thriving, particularly on radio and the emerging medium of television.

The photo feels like a snapshot from a bygone era, a peek into a world that seems far removed from today. Yet ventriloquism, while less common now, hasn’t disappeared entirely. The skill and creativity of ventriloquists continue to captivate audiences, with three performers—Terry Fator (2007), Paul Zerdin (2015), and Darci Lynne (2017)—even winning America’s Got Talent. It’s proof that while the world may change, some traditions live on in unexpected ways.

The sleeping mummy trader (1875)

Mummies have always fascinated humanity, with ancient Egyptian mummies captivating imaginations for over 2,000 years. But the way they’ve been treated throughout history reveals a strange and, at times, unsettling story.

During the Middle Ages, Europeans subjected mummies to all sorts of uses—ground into powder to create supposed medicinal cures, turned into torches because they burned so well, or even used in treatments for ailments like coughs or broken bones. The belief that mummies were embalmed with healing bitumen drove this trend, though that wasn’t actually true. By the 19th century, the medicinal use of mummies had waned, but the fascination remained.

Grave robbers fueled the demand for mummies, and merchants shipped them from Egypt to Europe and America, where they became prized possessions of the wealthy. They were displayed as symbols of status or used for research. One of the more bizarre trends of the 1800s was the “unwrapping party,” where mummies were ceremoniously unwrapped in front of curious onlookers—blurring the lines between science and entertainment.

This image of a merchant resting amidst a trove of mummies highlights how these ancient artifacts became commodities, exploited for everything from medical experiments to drawing-room spectacles. It’s a reminder of how cultural treasures were once treated — and why their preservation today is so important.

The iron lungs (1953)

Before vaccines, polio was one of the most feared diseases in the world, paralyzing or killing thousands every year. In the U.S., the 1952 outbreak was the worst, with nearly 58,000 cases reported—over 21,000 people left with disabilities and 3,145 lives lost, mostly children. Polio didn’t damage the lungs directly but attacked motor neurons in the spinal cord, severing communication between the brain and muscles needed to breathe.

For the sickest patients, survival often meant being confined to an iron lung, a mechanical respirator that kept them alive by forcing air into their paralyzed lungs. Hospitals housed rows upon rows of these towering, cylindrical machines, filled with children fighting for their lives. A single image of these “mechanical lungs” is enough to capture the devastating impact of polio, a chilling reminder of the fear and uncertainty that gripped families before the vaccine’s arrival in 1955.

Even for those who left the iron lung, life was never the same, often marked by lasting disabilities. But the picture above — rows of iron lungs stretching endlessly — is a testament to both the human cost of the epidemic and the resilience of those who fought to overcome it.

A young mother and her dead baby (1901)

The haunting image of Otylia Januszewska holding her recently deceased son, Aleksander, not only captures a profound moment of grief but also speaks to the Victorian tradition of post-mortem photography. This practice, which gained popularity in the mid-19th century, served as a way to honor the deceased and preserve a final, tangible connection to loved ones, especially when the reality of death felt too overwhelming to bear.

Rooted in the concept of memento mori, meaning “remember you must die,” the idea of reflecting on mortality has deep historical roots. During the Middle Ages, paintings often included reminders of death, and earlier cultures created trinkets depicting skeletons, offering a somber but necessary acknowledgment of life’s fragility.

As photography emerged in the 19th century, it became the perfect medium to make these reflections personal and intimate. Families, now able to take photographs, would immortalize their deceased loved ones in an attempt to hold onto them, keeping their faces forever within reach. It allowed the living to mourn, yes, but also to create a lasting bond, a sense of connection beyond death.

Interestingly, today, when a loved one passes, we tend to focus on celebrating their life, often avoiding the harsh reality of their death—almost as if it’s taboo to mention it directly. In stark contrast, Victorians embraced death with a fervor, incorporating it into rituals that acknowledged its inevitable presence.

Post-mortem photography, which reached its peak in the 1860s and 70s, was a key part of that. It began in the 1840s with the invention of photography, and while not all Victorians were comfortable with capturing images of the dead, the practice became widespread, especially in the UK, USA, and Europe.

9-year-old factory worker in Maine (1911)

In 1911, life for many working-class families in America was all about hard work, long hours, and making ends meet however they could.

For Nan de Gallant, a 9-year-old girl from Perry, Maine, summers meant one thing: working at the Seacoast Canning Co. in Eastport, Maine. She wasn’t running through fields or playing with friends — she was helping her family cart sardines, working long hours alongside her mother and two sisters.

Child labor was unfortunately common in early 20th-century America, especially in industries like canning, textiles, and agriculture. For families, every extra pair of hands helped. But for kids like Nan, it meant sacrificing childhood. By the age of 9, she was already working, something that was sadly not unusual for children in her age group during this time. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 18% of kids between the ages of 10 and 15 were working in 1910.

In Maine, a law banning children younger than 12 from working in manufacturing was in place — but it excluded canning industries, which made perishable goods. That law changed in 1911, but it’s hard to know how much it impacted the lives of kids like Nan.

James Brock pours acid in the pool (1964)

In 1964, a chilling photo captured Motel Manager James Brock pouring muriatic acid into the Monson Motor Lodge pool to prevent black swimmers from using it.

This act followed a group of black activists’ attempt to integrate the segregated space in St. Augustine, Florida. Rather than allow equality, Brock chose to destroy the pool.

The image, taken by Charles Moore, symbolizes the deep-rooted racism of the time and the courage of those fighting for civil rights. Today, it serves as a reminder of how far we’ve come and how much further we need to go in the fight for equality. It teaches us about resilience, the power of resistance, and the need to confront uncomfortable truths about our history.

Coal miners returning from the depths (C.1900)

In the early 1920s, Belgian coal miners faced tough days underground, working in dangerous conditions to fuel the growing industrial revolution. After hours of grueling labor in the dark, they would squeeze together in a crowded elevator, finally heading toward the light of day. The sound of the elevator creaking and the quiet hum of their voices showed just how much they relied on each other to get through it.

Their faces, covered in coal dust, told stories of hard work and sacrifice. Every wrinkle and line showed the toll the job took on them, but it also reflected their pride in the work they did. These men powered the industries that kept everything moving, even if it came at the cost of their health and safety.

When they finally stepped out into the daylight, it was a stark reminder of the contrast between the darkness of the mines and the brightness above. But more than that, it was a reminder of their strength and resilience. They had each other, and together, they kept going. Their bond, built through shared struggles, was the heart of their community — facing challenges side by side, no matter what.

Alvin Karpis’s fingertips (1936)

Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, a notorious criminal from the 1930s, was part of the Barker gang and involved in high-profile kidnappings. After leaving fingerprints at two major crimes in 1933, he sought to erase his identity.

In 1934, he and fellow gang member Fred Barker underwent cosmetic surgery from Chicago underworld doctor Joseph “Doc” Moran. Moran altered their noses, chins, and jaws, and even froze their fingers with cocaine to scrape off their fingerprints.

Despite these efforts, Karpis was caught in New Orleans in 1936, sentenced to life in prison, and spent over 30 years behind bars, including time at Alcatraz. He was paroled in 1969.

Halloween costumes in 1930

During the Great Depression, as violence and vandalism increased, communities began to create traditions like handing out candy, hosting costume parties, and organizing haunted houses to discourage disruptive behavior. This era also saw a wider variety of costume choices for children, adding more fun to the celebrations.

Two men making a death mask (c. 1908)

Death masks have long been used to preserve the likeness of the deceased. Ancient Egyptians, for example, created detailed masks to help the dead navigate the afterlife. Similarly, ancient Greeks and Romans crafted statues and busts of their ancestors, setting the stage for the death masks that would come later.

What set death masks apart from other depictions was their focus on realism. Unlike idealized sculptures, these masks were designed to capture the true features of the person, creating a lasting tribute. Famous figures like Napoleon, Lincoln, and Washington had death masks made, which were then used for statues and busts that immortalized them long after their deaths.

Is there an image you’ve missed or one you’ve seen that stood out to you? What do you think of all these eerie pictures? Which one left the strongest impression? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments on Facebook!